Erasure of Indigenous voices: behind Fazal Sheikh’s “Exposures”

A new, almost-cancelled exhibit at the Yale University Art Gallery both documents and produces conversations about how Indigenous communities are harmed by resource extraction, displacement and environmental racism.

Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

This article is one of a two-part series exploring the Yale University Art Gallery’s exhibit, “Fazal Sheikh: Exposures.” Read the story about concerns over censorship here.

Through expansive aerial shots and intimate portrait photography, Fazal Sheikh’s work documents sacred places in solidarity with their inhabitants. Viewers are transported to desert terrains and exposed to Indigenous communities who have long been displaced and erased by environmental racism.

“Fazal Sheikh: Exposures” is a new exhibit at the Yale University Art Gallery that premiered Sept. 9 and will be on display until Jan. 8, 2023. Born in 1965 in New York City, artist Fazal Sheikh documents displaced communities through photography.

Viewing portraiture as an act of mutual engagement, Sheikh seeks to make meaningful, long-term commitments to communities through years-long projects.

During Sheikh’s Artist Talk on Oct. 6, he revealed that this exhibit was almost canceled due to “the heart” of the exhibit being missing: an offering from a Diné spiritual advisor. The lack of transparency regarding its removal has prompted concern over censorship by the Yale University Art Gallery.

But Sheikh chose to proceed — inviting the Yale community to engage with and learn from the exhibit’s two main photographic projects: “Erasure” and “Exposure.”

Displacement in desert environments

Based in desert regions in Israel and the American Southwest, the exhibit explores the extensive consequences of environmental racism. “Erasure” grapples with Israel’s displacement of the Palestinian Bedouins, and the destructive legacy of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. “Exposure” is set in the American Southwest and looks at extractive mining practices and their consequences on Indigenous communities.

According to Judy Ditner, Richard Benson Associate Curator of Photography and Digital Media and organizer of the exhibit, the title “Exposures” refers to Sheikh’s practice of exposing the political and social harms done to Indigenous communities.

“The projects are both set in desert environments that have historically been written off as wastelands,” Ditner said. “Thus their largely nomadic Indigenous inhabitants have also been historically erased from the narratives, [while] that land has been actively pursued for political and economic ends.”

Sheikh’s work contemplates the manner in which states conduct their operations in desert regions. The exhibit emphasizes Native communities’ right to retain and protect their sacred spaces, exposing the vast scale of violence inflicted on their land in the quest for resources.

Erasure

Sheikh worked on “Erasure” between 2010 and 2015. The project contains both landscape and portrait works documenting the Palestinian Bedouin, a nomadic Arab community who has been displaced from their native land, the Negev desert in Israel. Many currently live in unrecognized villages, which they continue fighting to defend and maintain despite repeated demolition by Israeli authorities. According to Sheikh, the Israeli state plans to move the Bedouin into several fixed, state-planned townships. This forced displacement, he said, runs counter to their culture.

These Indigenous people come from the perspective of “honoring the land,” and have had to be “agile and innovative” enough to carve out an existence in what is often a very “inhospitable, unforgiving terrain,” Sheikh said.

“You can think of the Bedouins of the Negev desert as being forced to grapple with the same kinds of dispossession … the [same] predatory property relations that Indigenous people in the United States deal with,” said Yechen Zhao, who assisted with the exhibition as the Marcia Brady Tucker Fellow in Photography.

Sheikh was inspired to explore the aerial perspective in his photography after hearing about an unrecognized Bedouin village called Al-Araqīb, located near the city of Be’er-Sheva. At the time, the Israeli state had slated the village to be developed into the “Ambassador’s Forest,” a green belt designed to surround the city.

The artist visited an elder named Sheikh Sayach. Around 50 Bedouin shelters had just been destroyed by the Israeli government. The Bedouins were told that they could no longer remain on their historical lands, and would be forced to move to the nearby township.

The aerial perspective offers an opportunity to see the broader expanse of the Negev desert: military installations, waste sites, unrecognized villages razed to the ground, new settlements. Alongside the landscapes, the exhibit contains a long table with forensic evidence about Al-Araqīb and its repeated demolition.

Ditner noted that the project “Erasure” includes a “touching series” called “Independence/Nakba,” which is a set of paired portraits of Arabs and Israelis — who were born the same year between 1948 and 2013 — that demonstrates the ongoing generational trauma on both sides. This work is currently on view in the gallery’s fourth floor mezzanine.

“It’s not just walking through, wall to wall, looking at a piece and then moving on,” Zhao said. “There’s a sense that you need to sit with this information and really digest it.”

Exposure

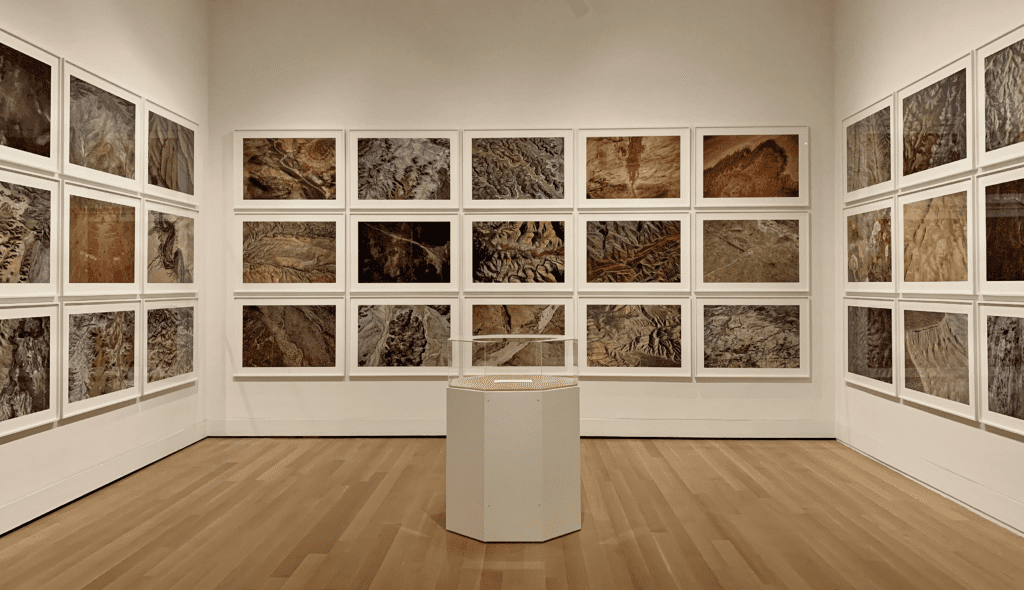

The “Exposure” section of the exhibit includes a main gallery on the Fourth Floor which displays large aerial landscape views of extractive mining practices, alongside portraits of the land’s Indigenous people.

From 2017 to 2022, Sheikh investigated the history of natural-resource extraction in the American Southwest and its consequences on the local Indigenous communities. He found that commercial mining of fossil fuels had ravaged much of the land — particularly swaths used for extensive extraction of coal, oil, gas and uranium. Poor remediation of extraction sites had allowed hazardous waste and pollution to continue poisoning the land and its water sources.

Uranium was extracted from the region from 1942 to the mid-1980s, with Native Americans often enlisted as miners. These people, largely Navajo, had not been apprised of the health hazards associated with working in close proximity to uranium.

Over the years, miners and their families began to grow sick. Uranium dust had invaded “the sanctuary of the home,” Sheikh said, transmitted via the clothes of miners, in a community with “exceptionally limited” access to water.

“Those communities know, from their history, not to pierce the skin of the land, that it’s possible to then unleash [dangerous] forces that may not be able to be harnessed,” Sheikh said. “And yet those communities were convinced to work in the mines because they thought they were helping their nation at a very pivotal moment in history.”

According to Zhao, Sheikh has set himself apart in the field of photography as someone who spends a lot of time with the communities that he’s working with, and really gets to know them.

In partnership with Utah Diné Bikéyah, a nonprofit coalition of Indigenous tribes including the Hopi, Navajo, Uintah Ouray Ute, Ute Mountain Ute and Zuni, he was invited to collaborate closely with the Indigenous people.

All of the work in the Southwest had to be conducted “slowly,” Sheikh said, in order to build trust within the communities and carefully research the full extent of environmental racism in the region.

“These are communities that across generations have had very conflicted relationships with the state and with people who have come to collaborate with them,” Sheikh said. “In the case of the Southwest, I only made portraits very late.”

The portraits familiarize viewers with the Indigenous people deeply impacted by extractive mining, including important Indigenous leaders, miners and their families. In these black and white portraits, the view of the sitter meets the gaze of the photographer.

Testimonies from each person accompany these intimate shots, describing how each has been impacted by the industry. These captions were all written by Fazal, based on interviews he conducted with subjects.

One portrait captures Lola Yellowman, a Diné widow of a uranium miner named John Guy. Her caption describes the Vanadium Corporation of America’s uranium mine, where many Navajo men worked, including her father. Mineshaft rocks were constantly exploding in mines, blasting mine dust onto the surrounding community.

Her father ended up dying early from respiratory illness, after years working in the mines. Yellowman’s husband also worked in the mines, and would come home with clothes caked in uranium dust. The companies never offered the workers protective equipment, and the dangers of exposure to uranium were never disclosed.

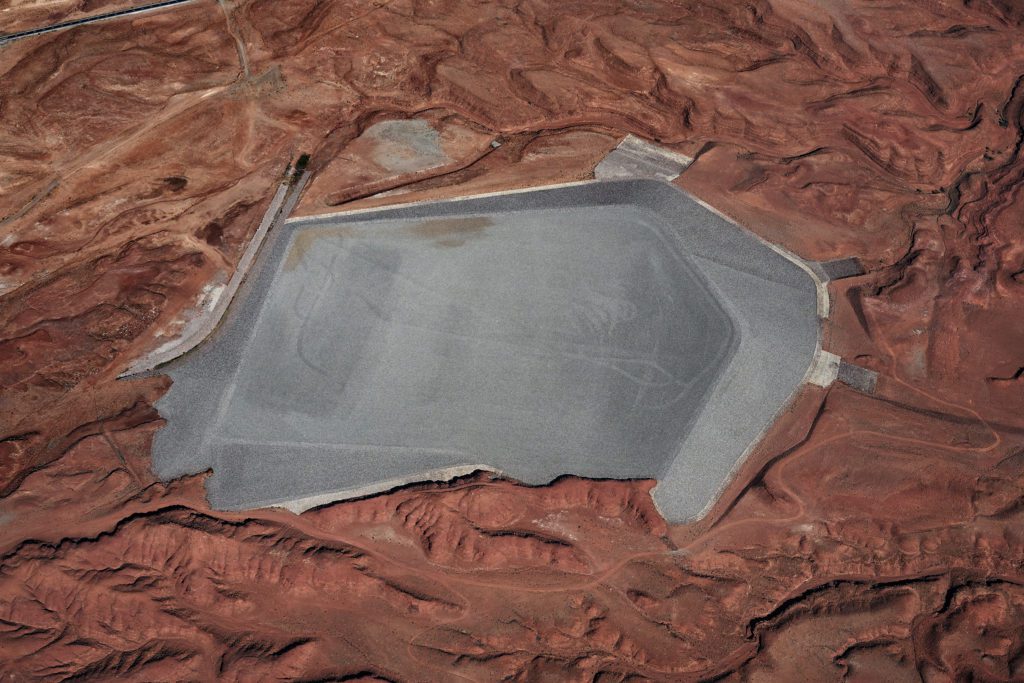

Sheikh’s aerial shots reveal the scale of the extractive industry. One image centers a huge uranium mine in Utah, called the Mexican Hat Uranium Mill Disposal Cell, containing 4.4 million tons of radioactive waste. Previously left uncovered, the site had to be completely capped after toxic dust leached into the environment, spreading radiation.

This 68-acre site lies adjacent to the village of Halchita, whose population is 98 percent Native American. Ditner described the aerial view as bringing a different sense of the land than one would have when standing with “your feet on the ground.” The damage is visible and visceral.

“The landscapes of extraction are devastating and also beautiful,” Ditner said. “For example, ‘Silver Bell Mine, Arizona’ depicts a copper mine, with pools of water that are this beautiful aqua [color ] … it’s always fascinating how the images can both be repellent and so captivating at the same time.”

A smaller gallery within the “Exposure” project, called “In Place,” documents the sacred lands of the Four Corners region. It is about the beauty, preservation and importance of those lands, rather than the extraction sites that seek to encroach upon it.

Over the course of this work, Sheikh had grown close to Jonah Yellowman — a Navajo elder and spiritual advisor to Utah Diné Bikéyah. Yellowman helped protect the 1.35 million acres of sacred land depicted in this room through advocating for former U.S. President Barack Obama’s 2016 proclamation to protect the ancestral homeland of the Tribal Nations as Bears Ears National Monument.

When former President Donald Trump downsized the monument by 85 percent, opening the region up to mining operations, President Joe Biden was pushed by continued advocacy to restore protections to the sacred land.

66 photographs of Bears Ears National Monument wrap around the room, demonstrating the utmost purity and sacredness of this land. The atmosphere is meditative and meant to be a space of solace and contemplation.

But sometimes pictures alone are misleading or simply not enough. A long octagonal bench in the room houses a speaker system that plays an audio recording made by geologist Jeff Moore. In Utah, Moore took seismological recordings of the landforms: Monument Valley archways in the Bears Ears region which vibrate and resonate with the movement of the Earth.

The sound rumbles, quiets and grows. If you sit on it, you can “feel the vibration of the Earth,” Ditner said. It is meant to be immersive, to give a real sense of the experience and power of the land, to make the heartbeat of the land audible.

When Sheikh visited this room a couple weeks ago, he walked in on a woman meditating, with her eyes closed and hands on the sound bench. This act was symbolic of all the healing and contemplation Sheikh and his collaborators — Moore and Yellowman — wanted this room to embody.

But Yellowman’s original contribution is missing.

Adjacent to the sound bench, a pedestal holds an octagonal case filled by nothing but air. At the room’s entrance, a sign displays “The Director’s Statement”: an explanation and apology for this absence. The case was meant to house a generous offering from Yellowman, but after last minute concerns over the ceremonial items it included, this case was left empty.

According to Ditner, the gallery had reached out to advisors at Yale, within Yale’s Native community and to local Native cultural and community representatives before deciding not to display the offering. The empty pedestal remains in the room to both acknowledge Yellowman’s contribution and indicate the difficult and ongoing conversations around the display of culturally sensitive items.

Questions linger over whether this removal was respectful or transparently decided. While Sheikh had considered closing his exhibit entirely due to the offering’s absence, he saw this as a learning opportunity for Yale: to start listening to Indigenous communities and set an example for other institutions as they attempt “to atone for historical trespass.”

Isabella Robbins GRD ’25, a Diné scholar who helped organize the exhibit, hopes that more space can be made for Indigenous perspectives that have been affected by resource extraction, displacement and environmental racism.

“I don’t just want people to read about our stories and think that’s enough,” Robbins said. “They need to question their own complicity in settler colonialism, and environmental racism — this includes [acts against] those peoples mentioned in the exhibition, but also [against] other Indigenous groups.”

On Nov. 3, the YUAG is hosting an event titled “Gallery+ Reading Exposures,” which will feature Diné poet Kinsale Drake ’22 and Afro-Palestinian writer Samah Fadil.