Behind an empty pedestal: YUAG controversy sparks discourse on Indigenous art

A dispute over purported censorship of a recent exhibit triggered a broader discussion over how museums should handle Indigenous art, pushing the Yale University Art Gallery to adopt advisory groups and new guidelines.

Courtesy of Alexandra Beck

This article is one of a two-part series on the Yale University Art Gallery’s exhibit, “Fazal Sheikh: Exposures.” Read the story exploring the exhibit’s curation here.

At the heart of an exhibit dedicated to documenting the erasure of Indigenous communities, an empty pedestal has prompted concern over the Yale University Art Gallery’s own alleged censorship of an Indigenous elder.

“Fazal Sheikh: Exposures” is a new exhibit at the Yale University Art Gallery that premiered Sept. 9 and will be on display until Jan. 8, 2023. Based in desert regions in Israel and the American Southwest, the exhibit explores the extensive consequences of environmental racism on Indigenous communities.

During Sheikh’s Artist Talk on Oct. 6, he told the crowd that this exhibit was almost canceled due to “the heart” of the original exhibit being missing: an offering from a Diné spiritual advisor.

One of the displayed projects, “Exposure,” is set in the American Southwest and looks at extractive mining practices and their consequences on Indigenous communities. Over the course of his time in the Southwest, Sheikh grew close to a Navajo Diné elder named Jonah Yellowman. As one of the “wisdom-keepers” of his tribe, Yellowman is held in the highest esteem, and has been a key mover in protecting 1.35 million acres of sacred lands in Bears Ears, Utah.

But when Yellowman gifted an offering to be housed in the room, the gallery removed it.

“Jonah’s [offering] was very much about protection and beauty and the gesture of a kind of attentiveness towards sacred landscapes,” Sheikh said. “So what on earth would make people feel as though they wanted to assail that, what was the reason?”

The Offering

A smaller gallery within the larger “Exposure” project called “In Place,” documents the sacred lands of the Four Corners region. It is about the beauty, preservation and importance of those lands, which have been threatened by extractive mining practices. Within the room, a pedestal carries an octagonal case filled with nothing but air. Yellowman’s offering is missing from it.

The offering was a sacred gift made to bless the land, and accordingly had to be properly requested in writing by gallery director Stephanie Wiles in January 2022. This gift contained the following: a Navajo ceremonial basket, five cloth banners, one pouch white corn, one pouch cedar, one pouch sage, one packet eagle plumes, one packet lighting way ceremonial medicine, two packets mixed medicine, one arrowhead and one bone flute.

Judy Ditner, Richard Benson associate curator of photography, had been in conversation with Sheikh about the exhibit since 2018. But in July 2022, two months before the exhibition’s opening, Sheikh and Yellowman were told that the offering could not be displayed.

According to Ditner, when it became clear that the offering included items of ceremonial significance, the gallery reached out to advisors within Yale’s Native community, and to local Native cultural and community representatives. Due to strong feedback and requests not to display these items, Ditner said the decision was made to leave the pedestal empty: both to acknowledge Yellowman’s contribution and indicate the difficult and ongoing conversations around the display of culturally sensitive items.

According to Royce Young Wolf — an Andrew W. Mellon postdoctoral associate in Native American art and curation who is of Hiraacá (Hidatsa), Nu’eta (Mandan) and Sosore (Eastern Shoshone) background — the gallery thought the display of sacred ceremonial instruments as art was too close to the “atrocities” that happened with grave robbing and misappropriation in the creation of the collections at Yale. They consulted national Indigenous cultural and Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act advisors to assess whether such items should be displayed.

Though Sheikh is working on a “global platform,” Young Wolf said, the needs of the local Indigenous communities should be prioritized by Yale, especially in light of the institution’s “difficult past.” Young Wolf emphasized the need for cultural sensitivities for the local Indigenous community of students, staff, fellows, professionals and the local tribes.

Concerns over decision-making

The original concern had been over displaying sacred ceremonial Indigenous materials, which included a modified eagle bone instrument — but such conversations took place without Yellowman.

“As we explained to the curators, the objects that I was to bring as part of my offering were not actual ceremonial objects, but decoys, to be shared with the museum for educational purposes, to teach people about the Diné community,” Yellowman wrote to the News.

Gallery representatives have not publicly disclosed the names of the advisors they consulted when deciding to remove the offering. Young Wolf told the News that such advising had to happen informally and anonymously because the gallery has no formal advisory group. According to Young Wolf, it is a safeguard to keep the names of the people consulted private, especially when dealing with sensitive manners, as the gallery did not want them to be blamed or made targets.

Ditner echoed this point, explaining that the gallery is working to build relationships with the Indigenous groups consulted, making it important to respect that anonymity as well as the advice given.

The names of the people consulted were also kept anonymous to Yellowman and Sheikh — a stipulation that Sheikh took issue with.

“If it is an amorphous group that remains unnamed, then an elder hasn’t the opportunity to be in discussion,” Sheikh said. “In a moment when we’re talking about trauma and disrespect, [this] is visiting the same trauma and disrespect on another.”

According to Sheikh, this should have been a conversation between elders — a fundamental level of respect and agency should have been accorded to Yellowman, who intended to offer healing to the space.

Sheikh said that conversations surrounding the offering should have happened early and in “an open, transparent, generative fashion.” Yellowman was not showing the offering as a display item, Sheikh said, but as a means to educate and speak openly about substantive issues.

A prior home

Fazal Sheikh’s “Exposure” project was previously shown at the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago for six months as a part of their exhibition “Toward Common Cause: Art, Social Change and the MacArthur Fellows Program at 40.”

According to Abigail Winograd, curator of the Smart Museum’s exhibition, over the course of the offering’s three-month span in Chicago, no one raised an objection to the offering. They used the offering, and the exhibit as a whole, to facilitate conversation with Indigenous scholars, community members and visitors.

During a conference at the Smart Museum, people debated over whether the offering was appropriate to show, in what was a “productive discussion” about the history of sacred objects and ceremonial objects from Indigenous communities being shown in museums.

Rather than being a contentious discussion, Winograd described it as a learning experience for everyone, including the institution.

But Young Wolf emphasized that what happens in “someone else’s home” is not justification for what can happen at the gallery. The tribal lands that Yale is on are different from the tribal lands in Chicago.

“Since this exhibit is being hosted on Indigenous lands that are not part of that host culture, which is Navajo Diné, we need to be considerate of the host cultures in this land,” Young Wolf said. “[In these] host cultures, there was an agreed consensus that such sacred ceremonial materials should not be displayed publicly as artwork, and for whatever reason that was lost in the communication.”

Isabella Robbins GRD ’25, a Diné scholar who helped organize the exhibit, emphasized that the sovereignty and cultural practices of the tribal lands where museums are located must also be a priority. She noted that the offering included items that could be considered ceremonial, despite intention, in many different contexts, including to the Navajo, members of the Native American Church, tribes in Connecticut and others represented in the Native community at Yale.

“Having listened to different voices throughout the curatorial process, I stand by the decision not to put those items on display, though the process revealed to me the complexity and importance of Indigenous-to-Indigenous relationships, and that museums and people who work with Native people have a lot to learn when it comes to honoring the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples and their spaces,” Robbins said.

A second offering

When Yellowman offered a second offering, which included no ceremonial items, it was “effectively refused,” Sheikh said. The second offering included four ears of corn — black corn, white corn, blue corn and yellow corn — representing the Four Directions as the Navajo origin story.

The gallery’s protocol for organic materials insists that they be treated for insects by either “taking out the oxygen,” using cold or heat, or performing a visual inspection, according to Ditner. The method used depends on what is most appropriate for different situations.

A gallery representative told Yellowman that the corn would have to be freeze-dried before it could be shown. Yellowman said he told the gallery representative, “that’s like me asking you to freeze-dry your bible.”

“It’s an offering, and to freeze it is clearly an aggression, and linked to a history of aggressions of a colonial order,” Sheikh said. “They wanted to make sure it wasn’t dirty and yet … it is corn that brings life and is the most pure and essential of gestures.”

After this interaction, Yellowman asked Sheikh to call him. According to Sheikh, Yellowman felt “humiliated” and asked Sheikh why they were going to Yale when “they don’t trust us.” The following day, Yellowman elected to remove himself from the project entirely and to sever contact with Yale in order to let go and move forward.

Ditner later told the News that the gallery should have offered a careful visual inspection of the offering. She described this as an example of miscommunication, in which a “very museum question” was asked without the intention of disrespect.

“We have no question that his offering was made in a generous manner and we respect that,” Ditner said. “And we wish that he had been able to participate and felt as though he wanted to participate at the end.”

During the Question and Answer section of Sheikh’s Artist Talk on Oct. 6, a first year PhD student in the History of Art spoke on the irony of the exhibit covering displacement and erasure while replicating the “institutional violence itself.”

The student — who was granted anonymity due to professional concerns — had been disappointed by the gallery committing the “same types of erasures the exhibition criticizes.” They saw Sheikh’s work as spaces born from active collaboration with the communities presented — where Indigenous voices and stories “could not only be heard, but learned from.”

“The empty pedestal serves now almost like a scar: it’s a physical reminder of the institutional violence against the voices exposed in the exhibition,” the student told the News. “What should have been a moment of healing and learning is now a site of aggression … While we should not allow the pedestal to overshadow the very important stories and voices the exhibition communicates, it is also a reminder that these stories … are incomplete … because of the political filter of the Yale art gallery.”

The aftermath

“It should be noted that there is no protocol at the museum which one may follow in these regards,” Sheikh said. “Nothing to which one may refer, and the process was not undertaken to navigate the heart of this installation until far too late by the museum, which had known about the material for many months.”

Ditner said that these conversations should have happened earlier and in person. Going forward, the gallery is working on forming an Indigenous advisory group and setting guidelines for how Indigenous representation and collaborative initiatives should occur.

According to Young Wolf, the gallery will bring local Indigenous scholars and BIPOC community members together with artists and curators in December. This will branch into a public program to educate and feed into the development and adoption of the guidelines in the gallery’s work.

This sensitive situation was the catalyst for this positive change, she said. Young Wolf emphasized the need to be open and respectful when engaging in these discussions, which are “happening across the nation.”

“Anyone working with us needs to trust that we know what we’re doing,” Young Wolf said. “They need to validate and support the fact that we are very educated, we are culturally knowledgeable.”

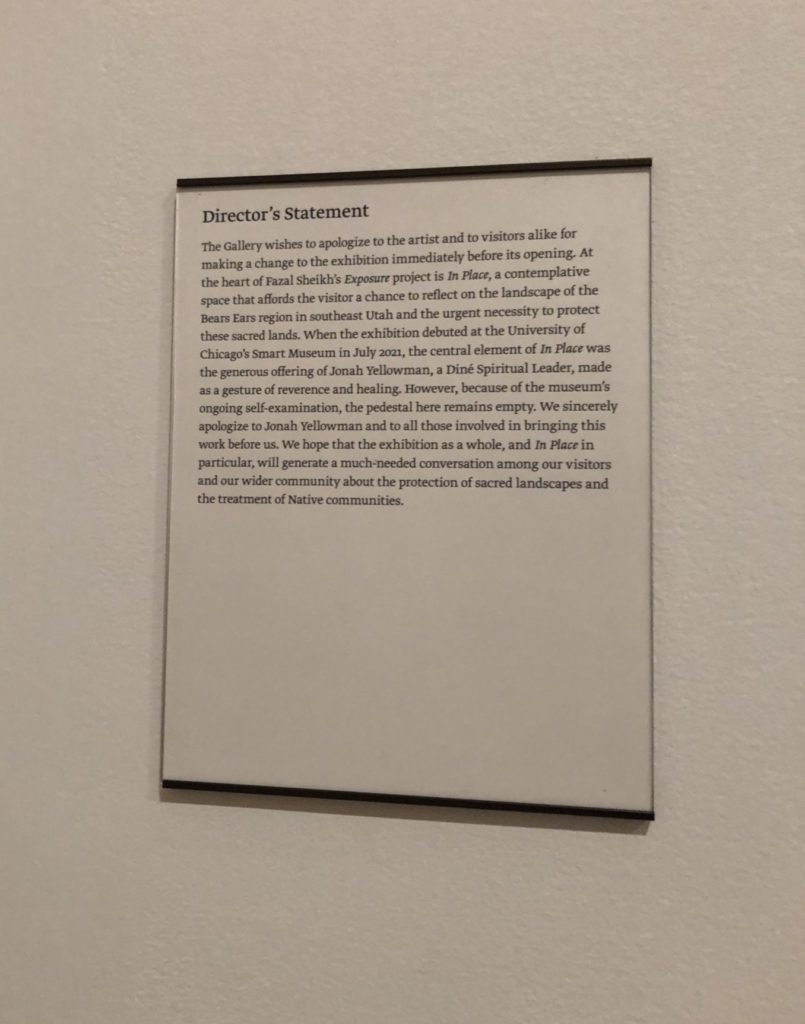

Sheikh had considered closing his exhibit entirely due to this removal, but he was heartened by the fact that the gallery’s director expressed a wish to apologize and to atone. He saw this as a learning moment for Yale, and allowed for the exhibit’s opening on the condition that a “Director’s Statement” be displayed in the “In Place” room.

For the past several days, Sheikh has been on a journey to the Southwest to return the offering to Yellowman in person. He hopes that this journey will “restore balance” and show respect to his collaborator. According to Sheikh, journeys made across time and great distance are a form of healing, and can provide closure in the wake of “such rancorous” conversations.

While this journey will fulfill a return of protection and community, he called upon the institution to take the next steps for “historical learning and repair.”

“They haven’t been listening to our people for generations and they’re still not listening,” Yellowman said. “What is all this teaching about? This is a chance for them to listen — let’s see what they will do.”

The Yale University Art Gallery is located at 1111 Chapel St, New Haven, CT 06510.