“To empower Black voters in Alabama”: Law School event highlights significance of recent Supreme Court ruling on voting rights

At an event co-hosted by the Liman Center for Public Interest Law and the Black Law Students Association, panelists explored the importance of the recent Supreme Court ruling in Allen v. Milligan for Black voters in Alabama.

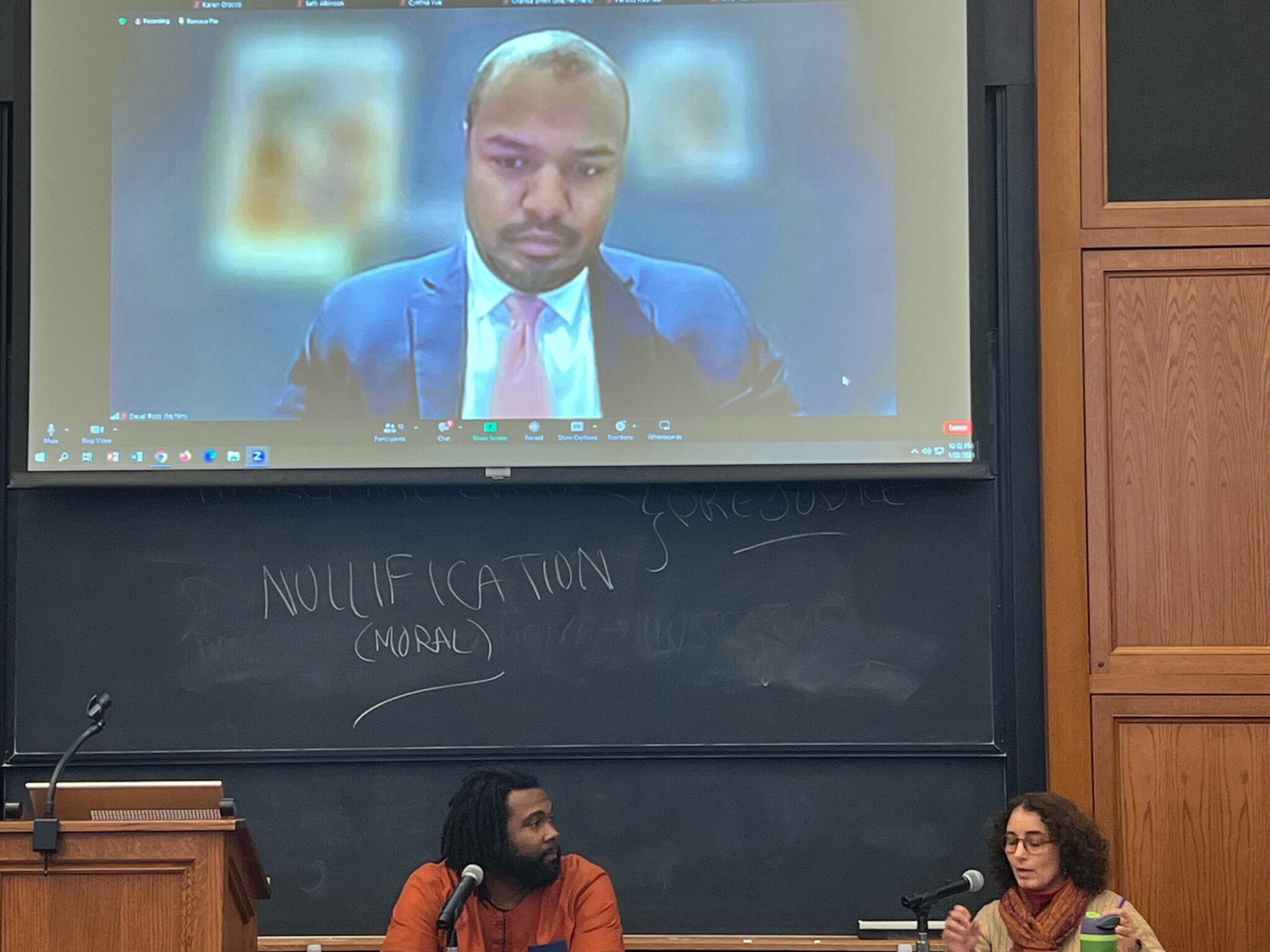

Adam Walker, Contributing Photographer

Yale Law School students and faculty gathered in Room 127 of the Sterling Law Building on Tuesday afternoon for an event on the Supreme Court’s ruling last summer in Allen v. Milligan, which was widely recognized as a victory for Black voters in Alabama.

The discussion, co-hosted by the Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law, the Black Law Students Association and several other organizations and student groups, featured panelists Evan Milligan, the lead plaintiff in the case; Deuel Ross, the attorney who argued for the Milligan plaintiffs at the Supreme Court; and Yale Law School professor Miriam Gohara, who moderated the discussion. Throughout the event, the panelists delved into the history of voter suppression in Alabama, the planning behind filing the brief for this case and the overall significance of the ruling in safeguarding voting rights.

On June 8, 2023, the United States Supreme Court issued a narrow 5-4 ruling in favor of Milligan, determining that Alabama’s congressional map violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Court’s majority concluded that the map, with only one majority-Black district out of seven, disenfranchised Black voters, as they comprised over a quarter of the state’s population at that time. The Court’s decision reaffirmed key protections established when the Voting Rights Act first was established.

“In a democracy, voting and elections are at the core of resolving disputes and negotiating power,” Jennifer Taylor LAW ’10, director of the Liman Center, wrote to the News. “The United States’ long struggle to reconcile the reality of racism with the ideal of democratic decision-making is an ongoing story, and last summer’s Milligan decision is an important chapter that has impact far beyond Alabama.”

Taylor also expressed hope that the event would inspire individuals to delve into the history of voting rights and think about ways they can actively support similar initiatives in their own communities.

The event began with opening remarks from Yale Law School Dean Heather Gerken, who explained that Alabama had historically failed to empower Black voters. Gerken, a specialist in election law, praised Milligan, Ross and all those involved in the case for their dedication, highlighting the courage it takes to be at the forefront of such cases. According to Gerken, most voting rights cases result in losses for the plaintiffs.

“You should know that in voting rights generally that over the course of decades, literally decades, you could count the number of wins for voting rights on one hand,” Gerken explained.

She added that the plaintiffs “should all get praised for doing so much work to push forward our democracy.”

Following Gerken’s opening remarks, Gohara invited Ross to provide insights into the case’s background and explain why this particular case holds significance.

Ross first explained redistricting, which is the process of drawing electoral district boundaries that occurs every 10 years based on the US census data. The process is meant to ensure equal representation at all levels of government, accounting for any changes in population. He explained that Alabama only had one majority-Black district — created due to legislation in 1982 — and that Black voters often need to rely on these districts for representation in government, particularly in the South.

“Black voters can sort of only often depend on elected officials who are elected from districts in which Black voters control the election results,” Ross explained. “And so what you see in a place like Alabama is unfortunately, the fact that the state has a lot of issues of poverty and issues of health care that are not being reflected in who is being elected to Congress in those places.”

Ross highlighted the Black Belt region in Alabama, Milligan’s hometown, as an example of this issue. He characterized it as more like the developing world compared to the rest of the United States, attributing this distinction to a history of racial discrimination and governmental neglect. Additionally, Ross noted that certain members of Alabama’s congressional delegation frequently refused to endorse bills in Congress that would be advantageous for majority-Black districts.

Ross further explained the demographic shifts in Alabama, noting that, in recent years, the Black population has expanded while the white population has decreased. According to Ross, the most recent redistricting resulted in white voters, constituting 45 percent of Alabama’s population, having an 86 percent control over congressional districts. In contrast, Black voters, comprising 27 percent of the state’s population, experienced limited representation.

“The history of racial discrimination made Alabama a really important place to bring this forward,” he said.

Gohara then directed the discussion toward Milligan, asking him to share his feelings as the lead plaintiff in this case.

Milligan first emphasized that he was one of six plaintiffs, underscoring the collaborative nature of their efforts on the case. With a family history six generations removed from plantation slavery in Alabama, Milligan brought attention to the profound importance of voting rights for Black individuals in America post-Civil War. He explained how post-war anti-reconstruction sentiments led to the enshrinement of white supremacy in Alabama’s state Constitution, influencing daily life and politics for decades. Milligan said that the case aimed to confront Alabama’s racist history and address its lasting impact on voting rights in the state.

Initially, Milligan said he was “very suspicious” about having his name at the center of this case. However, one of the attorneys explained the importance of showcasing the story of his family’s history in Alabama and the distinctive experiences of Black culture in the state, he said. This approach aimed to expose Alabama’s racist history as a means to demonstrate how its congressional map violated the Voting Rights Act.

“That was the first time that I saw a unique value in somebody’s life experiences and things that I just shared,” Milligan said. “And so that was ultimately why I agreed to do it.”

During the event, Ross also presented maps illustrating the distribution of the Black population in Alabama alongside a map of congressional districts. The visual aid served to emphasize the concentration of the Black population in just one district, which he used to argue that Alabama’s maps were unconstitutional before the Supreme Court.

After both speakers discussed their work on the case, Gohara highlighted the importance of history in this ruling and explained how history can be used as a legal strategy in litigation.

“The one thing that really struck me when I read this opinion in preparation for this panel was the fact that this was really acknowledging history, which is not something that we see happen as often as maybe we would like,” Gohara said.

Alabama was granted statehood on Dec. 14, 1819.