Event featuring journalist from Gaza sees heightened security measures, requires attendees to sign free-expression form

Ameera Harouda discussed balancing safety concerns for her and her family’s well-being, as well as her role as a mother of four, while also working to document the ongoing war in Israel and Gaza.

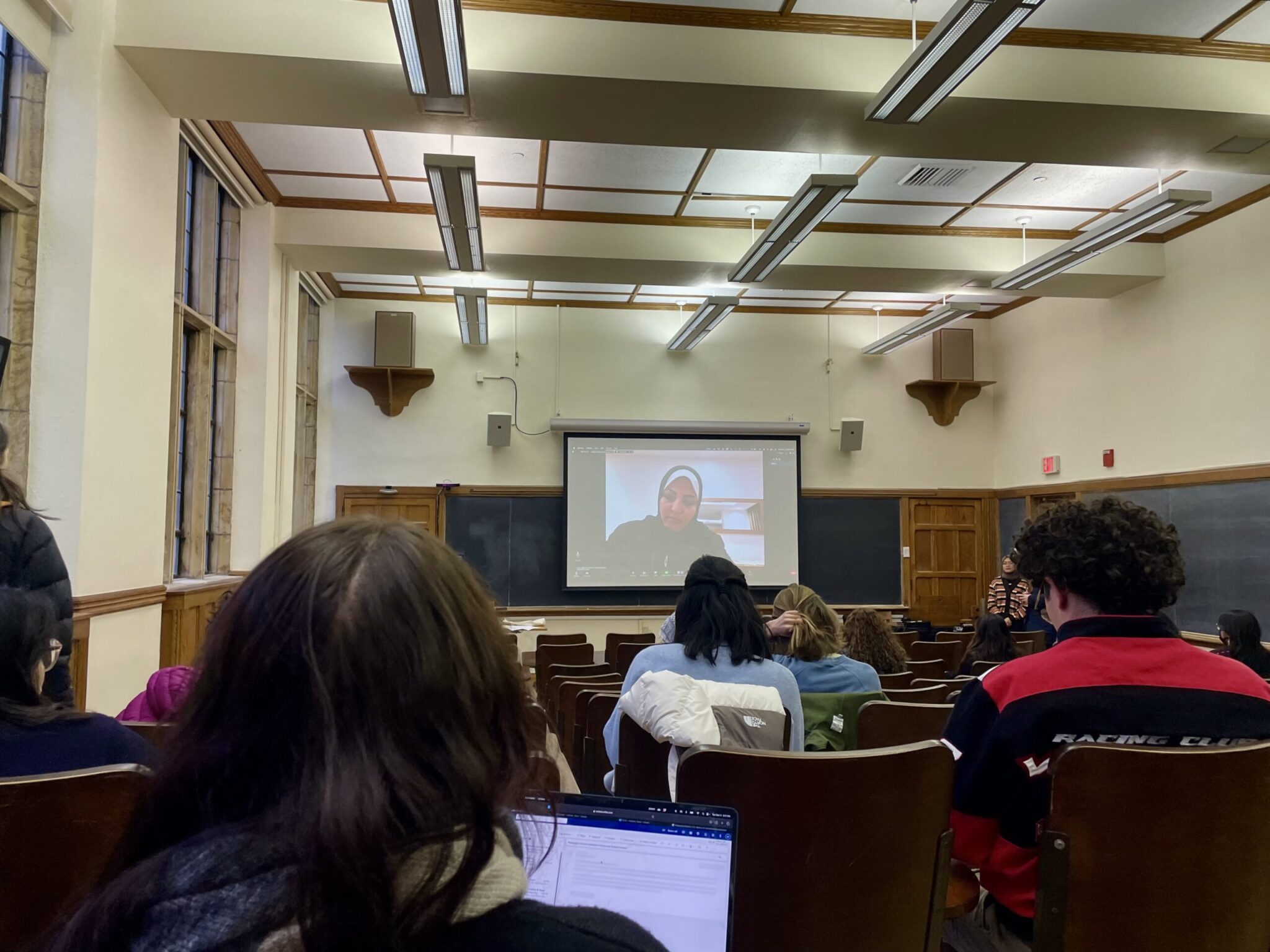

Ariela Lopez, Contributing Photographer

Ameera Harouda, a Palestinian journalist, spoke to a group of Yale students on Tuesday, Dec. 5 about her experience documenting and living through the war in Gaza. She spoke remotely from Doha, Qatar, where she and her family are currently residing.

The event was hosted by Yalies4Palestine and sponsored by the Yale Women’s Center, the Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity and Transnational Migration and the Poynter Fellowship in Journalism, which invites prominent journalists to deliver lectures to and engage with the Yale community. According to Theia Chatelle ’25, a former student coordinator for the Poynter Fellowship who organized and moderated the event, 94 people registered for the event. Approximately 45 people came to the talk.

“I’m not a political activist at all. I’m a journalist,” Harouda said in response to a question from Chattelle about balancing political activism with concerns for her children’s safety. “In the Gaza strip, it’s not easy balancing journalism with safety.”

Each attendee was asked to sign a form acknowledging Yale’s Free Expression Policy and agreeing not to record the talk. Chatelle told the audience at the beginning of the event that the form was a “new precaution” put in place in light of recent violence against Palestinian students, citing the recent shooting of three Palestinian college students in Vermont.

Yale’s Free Expression Policy stipulates, per the form, that students’ right to protest or express disagreement with a speaker is subject to three conditions. First, access to an event or facility may not be blocked; second, the event and the regular or essential operations of the university must not be disrupted and third, the safety of those attending the event and other members of the community may not be compromised.

“Should anyone choose to disrupt the event, you will be given the opportunity to stop, and if you do not, per Yale’s policy: ‘you will be subject to possible disciplinary sanctions, citation, and summons,’” the form read.

Chatelle told the News that she and other event organizers were concerned that participants’ safety could be compromised if the talk was recorded and shared online. The organizers were also concerned that people would try to interrupt the event.

“I think Ameera had a lot of very important things to say,” Chatelle said. “I didn’t want it to get disrupted by people who disagreed with the contents of the talk.”

Representatives from the Office of Student Affairs and the Office of Public Affairs and Communications were present at the event, Chatelle said, as well as marshals, legal observers and at least one plainclothes police officer stationed outside. Assistant Vice President for University Life Pilar Montalvo told the News that her office coordinated security efforts with Chatelle and Yalies4Palestine, which included facilitating communication with Yale Police.

Chatelle said she met Harouda last June while Chatelle was working as a freelance journalist in the West Bank. When the war between Israel and Hamas began, she decided to invite Harouda to speak at Yale.

Harouda has contributed to news outlets including the New York Times, the Washington Post, Al-Jazeera and CNN. In late October, a video interview of Harouda went viral on X, the platform previously known as Twitter. Harouda’s interview was interrupted by an explosion directly behind her, which Harouda attributed in the video to white phosphorus.

Human rights groups have accused Israeli forces of dropping shells containing white phosphorus on densely populated residential areas in Lebanon and Gaza during the ongoing Israel-Hamas war, the Associated Press reported on Oct. 31. The Associated Press added that Israel had maintained it only drops the incendiaries as a smokescreen and does not target civilians. International law regulates the use of phosphorus — it is illegal for it to be used against or near civilians, CBS News reported last year.

During the talk, Harouda spoke about the connection she views between her role as a mother to four young children and a fixer for international news outlets during times of conflict. Fixers are local contacts who help journalists working from a foreign country, often by arranging and interpreting interviews, translating documents and offering regional expertise.

For Harouda, covering the war is a great challenge — one that also provides her with the opportunity to tell the stories of other mothers.

Harouda added that even prior to the conflict, working in journalism was difficult for women in Gaza, who face societal standards that can preclude them from certain professions. She mentioned that her 15-year-old daughter helps take responsibility for caring for her younger siblings.

When asked about working with foreign correspondents, who may not be familiar with the nuances and customs of a certain region, Harouda emphasized the unique experience of living within a zone of conflict where “everyone will be a target.”

“It’s not easy to feel that you and your family will be a target for the Israeli army at any time,” Harouda said.

On Oct. 7, Hamas killed at least 1,200 people in Israel and took 240 as hostages, according to Israel’s Foreign Ministry. Israel responded with bombardment of north Gaza, killing more than 15,890 Palestinians, according to estimates from the Health Ministry in Hamas-controlled Gaza. Israel expanded its ground offensive to cover all of the Gaza Strip on Dec. 3, with its military vowing to hit south Gaza with “no less strength” than the north, the Associated Press reported.

Since Hamas’ Oct. 7 terror attack, about 60 journalists have been killed in Gaza and Israel, according to reporting by the Associated Press on Dec. 4 — roughly the same as the total number of journalists killed during the 20-year Vietnam War. Of those 60 killed journalists, at least 51 were Palestinian, the general secretary of the International Federation of Journalists told the AP.

Tuesday’s event was titled “Ameera Harouda on Life during War as Mother and Journalist” on the Poynter website and “Ameera Harouda: Motherhood, Journalism, and the Gazan Genocide” on Yalies 4 Palestine’s Instagram page. Chatelle said that she had sent Y4P’s version of the title to Poynter, but the Fellowship’s website was not updated with that language.

The Office of Public Affairs, which oversees the Poynter Fellowship, wrote that the name on their website is the name submitted in the application for the event, which was approved less than a week before the event. The updated name was submitted a day before the event, which was too close to the actual event to change, the Office wrote.

The Poynter Fellowship in Journalism was established in 1967.