The key question in Students for Fair Admissions’ lawsuits against the University of North Carolina and Harvard College was whether their affirmative action policies constituted unlawful racial discrimination against Asian American applicants. On June 29, the justices ruled 6-3 that both universities’ policies do, in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. On that question, the Court’s majority was right.

Many readers are likely familiar with Professor Ibram X. Kendi’s definition of a racist policy as “any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups.” For example, Jim Crow literacy tests, while facially-race neutral, were a form of racial discrimination because they disproportionately disenfranchised Black voters (as was the intent). Despite roughly equal rates of usage, Black people are 3.73 times more likely to be arrested on marijuana charges than white people, according to the ACLU; that’s evidence of racial bias in the criminal justice system. The News itself implicitly subscribes to Kendi’s definition that disparity itself is evidence of discrimination: its website contains a page labeled “Staff Demographics,” which compares the breakdown of News staffers by race to that of the University at large.

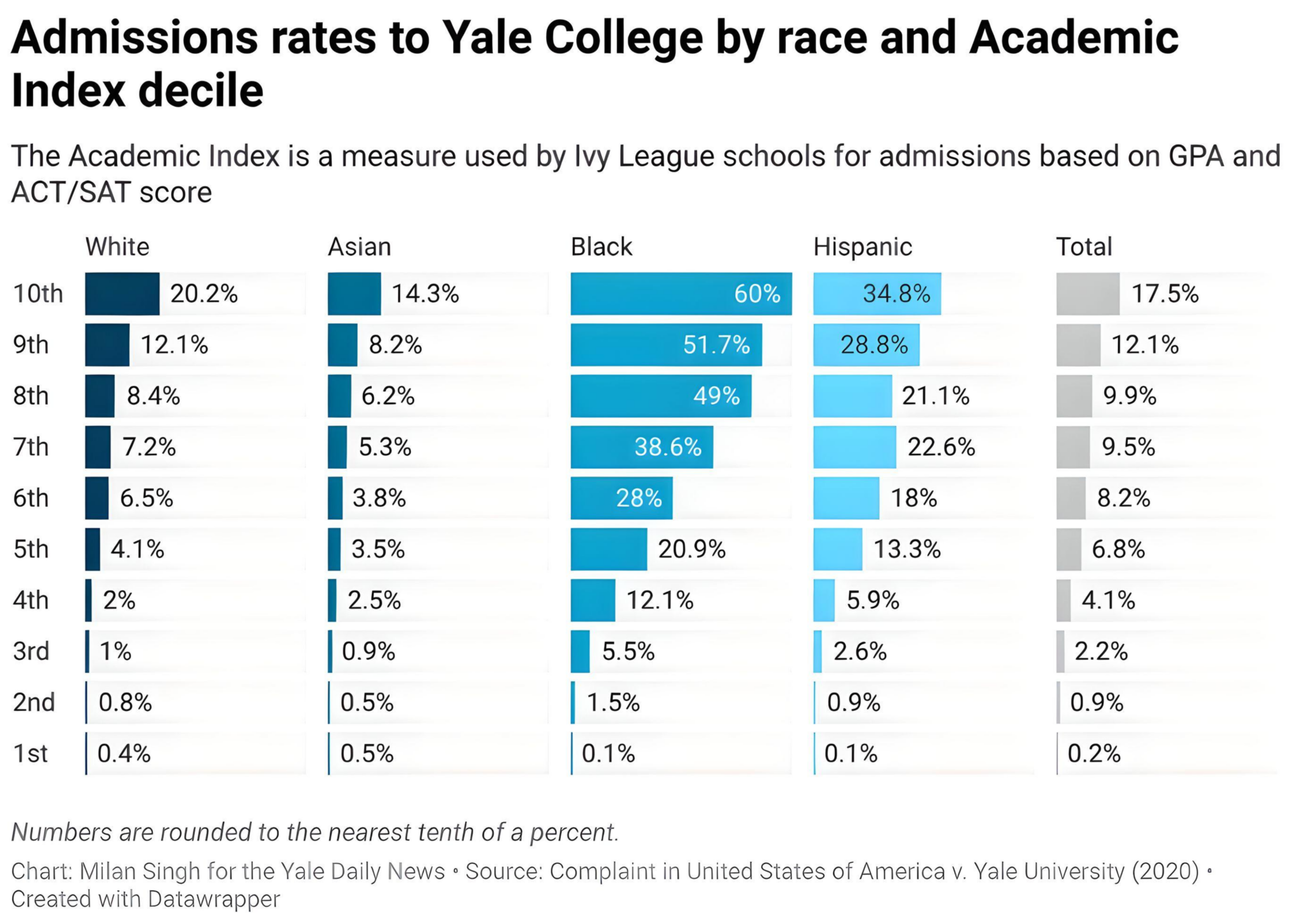

Under the Kendi framework, affirmative action is clearly discriminatory against Asian Americans. Consider the admissions data that Yale University released as part of a 2020 lawsuit from the Trump administration’s Department of Justice. The following chart displays admissions rates for students, broken out by race and Academic Index decile. (Academic Index is a composite of GPA and standardized test scores; a student in the sixth decile would have had a higher Academic Index score than 60 percent of applicants.)

Black students at or above the 20th percentile of Academic Index scores are more likely than average to be accepted to Yale; for Hispanic students, it’s the 30th percentile; for white students, the 90th. But at every decile, Asian American students are less likely than the general applicant pool to be admitted.

In a study commissioned for the SFFA lawsuit, professors Peter Arcidiacono, Josh Kinsler and Tyler Ransom modeled the racial breakdown of an admitted Harvard class, under most current policies but absent affirmative action, athlete and legacy admissions. Compared with the status quo, a world without racial, athlete or legacy preferences would show essentially no change in the share of white students, but it would show a large decrease in the share of Black and Hispanic students offset by an increase in Asian admits.

To the extent that affirmative action policies are conceptualized as a sort of reparations for racial injustices such as slavery and Jim Crow, this presents a problem: the burden of adjustment is being placed on Asian American, rather than white, students. A second problem is that the vast majority of Black and Hispanic students — whom affirmative action is intended to help — do not benefit from the policy.

Fundamentally, affirmative action is about who you say “no” to; unless you have more applicants than available seats, you can’t put the policy into practice. According to calculations published in a New York Times opinion piece by professors Richard Arum of the University of California and Mitchell Stevens of Stanford University, less than 10 percent of Black and Hispanic students attend colleges with acceptance rates below 25 percent; nearly 60 percent of Black students and around 55 percent of Hispanic students attend schools with acceptance rates of 75 percent or more. And the majority of Black and Hispanic teenagers do not attend college at all.

For better or for worse, institutions such as Yale have enormous influence in our society. I would hope that this ruling opens a debate about whether they ought to have such power. I am not naïve enough to think that reduced diversity at elite colleges will simply be canceled out by a change in hiring practices or that diversity has no value in the educational experience. The Court’s ruling reads that “nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.” But rather than attempting to reconstruct the present admissions system via the personal essay, elite universities ought to adopt top 10 percent admissions plans, like those that the University of Texas system employs, or look into affirmative action programs based on class rather than race. Legacy admissions should be scrapped. Instead of pushing to eliminate standardized testing, schools should move towards making these tests universally available — for free. (Contrary to popular opinion, research has found that expensive test prep doesn’t lift scores by much, and essays can be ghostwritten.) Governments should take steps to equalize public school funding. Elite universities can redirect a portion of donor or endowment funds toward colleges that admit the majority of and are proven to provide upward mobility for low-income students.

This is not an exhaustive list of solutions, and a lively debate should be welcomed. But discussions over how to move forward should be grounded in two key points. First, be honest about the fact that affirmative action was in fact discriminatory towards Asian American students. Second, acknowledge that the path to equality in education simply cannot be primarily run through the admissions policies of a tiny group of highly selective and fundamentally exclusive schools.

MILAN SINGH is a sophomore in Pierson College. His fortnightly column, “All politics is national” discusses national politics: how it affects the reader’s life, and why they should care about it. He can be reached at milan.singh@yale.edu.